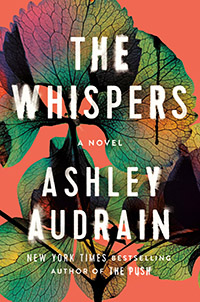

The Whispers

Ashley Audrain

For every mom hanging on by a thread. And for those trying desperately to be one.

What I increasingly felt, in marriage and in motherhood, was that to live as a woman and to live as a feminist were two different and possibly irreconcilable things.

—Rachel Cusk, in an interview with The Globe and Mail, 2012

He lifts two fingers to his nose and smells the child’s mother as his eyes grow wide in the dark of his kitchen. The clock on the oven reads 11:56 p.m. His chest. Everything feels tight. Is he having a heart attack? Is this how a heart attack feels? He must move. He paces the white-oak hardwood and touches things, the lever on the toaster; the stainless-steel handle of the fridge; the softening, fragrant bananas in the fruit bowl. He is looking for familiarity to ground him. To bring him back.

A shower. He should shower. He scales the stairs like a toddler.

He refuses to look at himself in the bathroom mirror.

His skin stings. He scrubs.

He thinks he hears sirens. Are those sirens?

He wrenches the shower handle and listens. Nothing.

Bed, he should be in bed. That’s where he would be if nothing had happened. If this was just another Wednesday night in June. He dries himself and places the towel on the door’s hook where it always hangs. He fiddles with the way the white terry cloth falls, perfecting the ripple in the fabric like he’s staging a department store display, his hands twitching with an unfamiliar fear.

His phone. He creeps through the dark house looking for where he’s put it—the hallway bench, the kitchen counter, the table near the foot of the stairs. His coat pocket, that’s where it is, on the floor at the back door, where he’d dropped it when he came into the house. He brings the phone upstairs, his legs still feeble, and stops outside their bedroom door.

He can’t be in there.

He’ll sleep in the spare room. He lies down slowly on the double bed, noting the care with which the linens have been smoothed and tucked, and places the phone beside him. He has an aching urge to call her.

What would he say? That he misses her? That he needs her?

It’s too late.

But he stares at the phone anyway, imagining himself hearing the steady march of the ringtone while he waits for her to pick up. And then he closes his eyes and sees the child again.

Sometime later he feels the mattress tremble. Someone has joined him. He waits to be touched. But no, it’s a vibration. And then again. And then again. There’s a streak of tangerine light piercing through the room. He swipes his thumb across the reflection of his bleary face on the phone’s screen to answer.

The pained pitch of her voice. He has heard it before.

“Something terrible happened,” she says.

September

The Loverlys’ Backyard

There is something animalistic about the way the middle-aged adults size each other up while feigning friendliness in the backyard of the most expensive house on the street. The crowd drifts toward the most attractive ones. They are there for a neighborly family afternoon, for the children, who play a parallel kind of game, but the men have chosen nice shoes, and the women wear accessories that don’t make it to the playground, and the tone of everyone’s voice is polished.

The party is catered. There are large steel tubs with icy craft beer and bite-size burgers on long wooden platters and paper cones overflowing with shoestring fries. There are loot bags with cookies iced in each child’s name, the cellophane tied with thick satin ribbon.

The back fence is lined with a strip of mature trees, newly planted, lifted and placed by a crane. There’s no sign of the unpleasant back alley they abut, the dwellers from the rehab housing units four blocks away, the sewers that overflow in the rain. The grass is an admirable shade of green. There’s an irrigation system. The polished concrete patio off the kitchen is anchored with carefully arranged planters of boxwood. There is a shed that isn’t really a shed—its door pivots, there’s a proper light fixture.

Three children belong to this backyard, to the towering three-story home that has been built on the double lot, unheard-of in an urban neighborhood like this. The three-year-old twins, a boy and a girl, are in matching seersucker, and they’ve let the mother of this audacious house style their hair nicely, swept, patted. The older boy, ten, insists on wearing last year’s phys ed uniform with a stain on the T-shirt. Hot chocolate or blood, the guests will wonder. But Whitney’s husband had convinced her to pick her battles wisely in the fifteen minutes before the party begins.

By three thirty in the afternoon, she has let go of the urge to rip the gym shirt off him, to wrestle him into the powder-blue polo she bought for the occasion. She has let go of the hosting stress and feels the satisfying high of everyone enjoying themselves. She has impressed them all enough. She can tell from the glances, the subtle pointing between friends who notice the details she hopes they will. She thinks of the photos that will smatter social media tonight. The hum is loud and peppered with laughter, and this air of conviviality satiates her.

* * *

? ? ?

This noise is the reason Mara, next door, doesn’t come. She got the heavy-cardstock invitation in her mailbox the month prior, like everyone else, and slipped it straight into the recycling bin. She knows these neighbors don’t really want people like her and Albert there. They think she’s got nothing to offer anymore. Her decades of wisdom don’t matter in the least to those women, who march around like they’ve got it all figured out. But that’s fine. She can see and hear everything she needs to through the slats in the fence, while she tidies her own garden, plucks at the tips of new weeds until her lower back is too sore, then she’ll move to the mildewed patio chair. She notices something in the crispy-petaled branches of her hydrangea bush. She gives it a shake. A paper airplane falls nose first into the dirt. Another one she’s missed. She found several in her yard Thursday morning. She bends to collect it as she hears Whitney’s voice crest above the guests, greeting the couple from across the street.

* * *

? ? ?

That couple, Rebecca and Ben, make a point of finding the host as soon as they arrive. They’ve got twenty minutes and a potted orchid to give her. Rebecca has to get to work. Ben has Rebecca to appease, or he’d have stayed home. He is quiet while Rebecca and Whitney exchange pleasantries. Whitney compliments and inquires, she paws Rebecca’s hand and then her shoulder, and Rebecca concedes. She is charmed in a way she isn’t usually. She hopes nobody interrupts.

Ben’s hair is still damp from the shower, and he smells like the morning. He feels Whitney glance at him while she speaks to his wife. His hand is in the back pocket of Rebecca’s white jeans. He pulls her closer. Rebecca can sense that he isn’t listening to her conversation with Whitney, not really, and she is right. He is watching the magician twirl a colorful scarf around one of Whitney’s giggling twins, the girl, she has found Ben’s friendly eyes. He’s not overly social with other adults, but the children are always drawn to him. He is the favorite teacher. He is the playful uncle. He is the baseball coach.

* * *

? ? ?