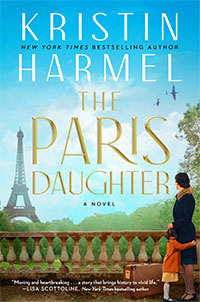

The Paris Daughter

Kristin Harmel

To my mom, Carol, and my son, Noah, from whom I learned the exquisite and endless joy of the bond between a mother and her child—the most complex and, at the same time, somehow the simplest love in the world.

PART I

Motherhood: All love begins and ends there.

—ROBERT BROWNING

CHAPTER ONE

September 1939

The summer was lingering, but the air was crisp at the edges that morning, autumn already tapping at the door, as Elise LeClair hurried toward the western edge of Paris. She usually loved the summer, wanted it to last forever, but this year was different, for in just four months the baby would be here, and everything would change. It had to, didn’t it? She cradled her belly as she slipped into the embrace of the shady Bois de Boulogne.

Overhead, chestnuts, oaks, and cedars arched into a canopy, gradually blotting out the sun as she took first one winding trail and then another, moving deeper into the park. The same sky stretched over all of Paris, but here, beneath it, Elise was simply herself, not a woman defined by her neighborhood, her station, her husband.

When she married Olivier four years earlier, she hadn’t realized that the longer she stood by his side, the more invisible she would become. They’d met in New York in early 1935, and she had been awed by his raw talent—he did things with brushstrokes that most artists only dreamed of. He’d been twenty-nine to her twenty-three, and it was the year he’d first been splashed across the magazines. Art Digest had called him “the next great artist hailing from Europe”; Collier’s described him as having “the brush of Picasso with the looks of Clark Gable”; and even the New York Times had declared him “a Monet for a new day,” which wasn’t quite right because his style didn’t resemble the French master’s, but the point was clear. He was the toast of the art world, and when he turned his gaze on Elise, she couldn’t look away.

She was an artist, too, or rather, she wanted to be. She loved to sketch, she loved to paint, but her real medium was sculpture. Her parents had died when she was nineteen, leaving her lost and adrift, and Olivier had offered her a raft to a different life. He had been the first one, in fact, to introduce her to wood as an alternative to clay. With a mallet and a chisel she could work out her grief, he’d told her, and he’d been right. When he proposed to her two months later, her reaction had been one of gratitude and disbelief—Olivier LeClair wanted to marry her?

Only in the years since had she realized marriage was supposed to be a partnership, not a practice in idolatry, and as she gradually got to know the Olivier the world didn’t—the one who snored in his sleep, who drank too much whiskey, who slashed canvases in a rage when the images in his head didn’t match the ones he’d painted—he had begun to slip off his pedestal. But in time, she had come to love him for the darkness as much as for the light that sometimes spilled out from him, eclipsing everything else in his orbit.

The problem was that Olivier didn’t seem to want a partner. She’d thought he’d seen in her a raw talent, an artistic eye. But now, with the clarity of hindsight, it seemed that he’d only wanted a qualified acolyte. And so life in their apartment had grown tenser, his criticisms of her carvings more frequent, his frowns at her work more obvious. Even now, with his baby growing in her belly, changing the shape of her from the inside out, she felt corseted by her marriage to him, choked by the lack of oxygen left over for her in their large sixth-floor apartment in Paris’s tony seizième arrondissement.

It was why she had to come, as she often did, to the sprawling park that spilled over into Paris’s western suburbs. Here, where no one knew her as the wife of Olivier LeClair, she could feel the corset strings gradually loosening. She could feel her fingertips twitching, ready to carve again. Only once she walked through their apartment door would the tingling stop, the creative spirit in her retreating.

But the baby. The baby would change everything. The pregnancy hadn’t been intended, but Olivier had embraced the news with a fervor Elise hadn’t expected. “Oh, Elise, he will be perfect,” he had said when she delivered the news, his eyes shining with tears. “The best parts of you and me. Someone to carry on our legacy.”

She sat heavily on a bench beside one of the walking paths. Her joints ached more than usual today; the baby had shifted and was sitting low, pressing into her pelvic bone. She bent to pull her sketch pad and a Conté crayon from her handbag, and as she straightened back up, she felt a sharp stab of pain in her right side, below her rib cage, but just as quickly, it was gone. She took a deep breath and began to sketch the robin on a branch above her, busy building its nest as it paid her no mind.

Her sketches always looked a bit mad, even to her, for she wasn’t trying to commit precise images to paper, not exactly. Instead, the sketches were to capture the complexities of angles, of curves, of movement, so that she could find those same shapes in the wood later. As she quickly roughed out the right wing of the robin, she was already imagining the way the thin ribbons of wood would peel away beneath her fingers. The bird turned, laying some sticks at a different angle, and at once, Elise’s hand was tracing its neck, the sharp, jerky movements as it shortened and elongated.

As the day grew brighter, she lost track of time, sketching the bird’s beak, its inquisitive eyes. And when it flew away, as she knew would eventually happen, she found another robin and flipped the page, once again tackling the delicate perch of its wings, the way they were folded just so against its wiry body. And then, suddenly, that bird, too, lifted off, glancing at her before it soared away, and she looked down at her pad expectantly. Surely she had enough to work with.

But instead of the crisp avian sketches she expected to see, her page was filled with an angry tangle of lines and curves. She stared at it in disbelief for a second before ripping it from the pad, balling it up, and crumpling it with a little scream of frustration. She leaned forward, pressing her forehead against fisted palms. How was it that everything she did seemed to turn out wrong these days?

She stood abruptly, her pulse racing. She couldn’t keep doing this: going for long walks that led nowhere, returning home with her thoughts still tangled, her hands still idle. She took a step away from the bench, and suddenly the pain in her midsection was back, more acute this time, sharp enough to make her gasp and stumble as she doubled over. She reached for the bench to steady herself, but she missed, her hand slicing uselessly through the air as she fell to her knees.

“Madame?” There was a voice, a female voice, coming from somewhere nearby, but Elise could hardly hear it over the ringing in her ears.

“The baby,” Elise managed to say, and then there was a woman standing by her side, grasping her elbow, helping her up, and the world swam back into focus.

“Madame?” the woman was asking with concern. “Are you all right?”

Elise blinked a few times and tried to smile politely, already embarrassed. “Oh, I’m fine, I’m fine,” she replied. “Just a little dizzy.”

The woman was still holding her arm, and Elise focused on her for the first time. They were about the same age, and the woman’s face, though creased in concern, was beautiful, with the kinds of sharp, narrow lines Olivier loved to paint, her lips small and bowed, her eyes the slate gray of the Seine before a storm.

“Maman?” The voice came from behind the woman, and Elise peered around her to see a little boy of about four with chestnut curls standing there in blue shorts and a crisp cotton shirt, his hand clutching the handle of a carriage that held a smaller boy with matching clothes and identical ringlets.

“Oh dear,” Elise said with a laugh, pulling away from the woman though she still felt unsteady. “I’ve frightened your children. I’m terribly sorry.”

“There’s nothing to apologize for, madame,” the woman said, flashing a small smile before she turned to her sons. “Everything is all right, my dears.”

“But who is the lady?” the older boy asked, looking at Elise with concern.

“My name is Madame LeClair,” Elise replied with a smile she hoped would reassure the child. Then she glanced at the mother and added, “Elise LeClair. And truly, I’m perfectly fine.”

“Juliette Foulon,” the woman replied, but she didn’t look convinced. “Now, shall we go, Madame LeClair?”

“Go?”

“To see a doctor, of course, Madame LeClair.”